Climate Change is Felt Most by Knoxville's Low-Income Communities

Climate change places a stronger economic burden on Knoxville's low-income community.

Whether in political debate or at the dinner table, the issue of climate change hits closer to home for some families.

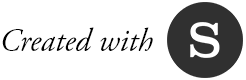

In Knoxville, Tennessee, extreme temperatures have become more apparent over time. Over the last year alone, the National Weather Service reported a record-breaking high for the area, reaching 96 degrees in October, which is the highest temperature the city has faced during that time of year since 1884.

Home to a large student population, many of Knoxville’s residents are fortunate enough to have protection from dangerous heat, but what about those living beyond the campus, in rural, often poorer areas?

About 26.5% of Knoxville’s population lives in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, well above the state average of 16.1% and the national average of 15.1%. Whether these people are living in trailer parks, poorly insulated homes, or on the street, protection against extreme temperatures is far from reach for some families.

ThreeCubed, a local non-profit, aims to alleviate this issue. By combining their research on estimating the non-energy impacts of weatherizing low-income homes with community action agencies, the organization works to improve the livability of inadequate housing for those who cannot afford to invest in it on their own.

The problem takes root in something called “energy burden,” according to ThreeCubed president, Dr. Bruce Tonn. Essentially, energy burden refers to the amount of money people spend on their utilities as a proportion of their income. In a comfortable situation, families shouldn’t spend more than 6% of their household income on utilities.

“In Knoxville, energy burden rates can be as high as 30%, meaning that families spend 30% of their income on utility bills,” Tonn said in an interview.

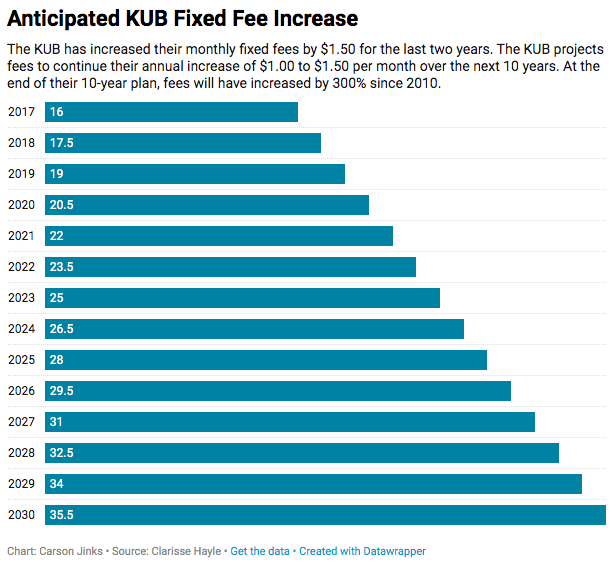

Since 2010, the Knoxville Utilities Board has nearly tripled its monthly fixed fees. Whether the air-conditioning is cranked up or not, customers are being charged big bucks. “It is going to be a choice of paying for that utility bill versus not having the money to pay for that utility bill to stay cool and safe in the summer,” said Dr. Lisa Mason, a professor at the University of Tennessee who studies climate change and social justice.

The poor energy-efficiency of low-income housing increases utility bills further, which is where ThreeCubed comes in. To reduce energy usage, Tonn and his colleagues have found that weatherizing homes is the most successful option.

“Weatherization entails air sealing, installing insulation in the walls, ceilings, and floors, and replacing or repairing furnaces and air-conditioning equipment,” Tonn said.

The Tennessee Valley Authority has expanded its new-home uplift program to provide weatherization services in the area, but the local community action agency still faces a long wait-list of homes needing to be renovated.

“We’ve been in homes where people have essentially nailed up blankets around the windows, which is not a solution, but that’s what they’re left with doing. Sometimes they even resort to heating parts of their home with their ovens,” Tonn continued.

There is also a mental health factor to climate change. When more money is poured into utility bills, the ability to spend on other necessities decreases. “When energy burden gets above 6%, that starts to cause a sense of alarm for people. They get mentally stressed out obviously, but they also stop buying food and prescriptions,” explained Tonn.

As the relevance of climate change continues to increase, the demand for energy rises with it, pushing the KUB to keep raising its fees. Over the next 10 years, the KUB has projected an annual increase of $1 to $1.50 per month, according to Clarisse Hayle, a TN Energy Savings Outreach and Communications Assistant, despite the fact that fees have already been raised $1.50 every year for the last two years. Customers are currently paying the upward of $19 a month before using any energy, but it does not stop there. As early as this month, KUB fixed fees will see another jump, rising to $20.50.

“By the end of the 10-year plan, the projected fixed charge could be as high as $30 per month. This is a 300% increase from the overall cost of KUB utility bills in 2010,” Hayle stated in an article.

Since the beginning of 2019, the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy has presented the KUB with nearly 3,000 customer requests to “freeze the fees.” Residents continue to attend KUB meetings to assert their concerns directly, but the board does not plan to renegotiate fee increases until at least next year, according to the Knox News Sentinel.

Given KUB resistance to assist in lowering utility costs, the low-income community has gained support from large organizations who are considering different approaches to improving energy burden.

Through lobbying, drafting bills, and grassroots outreach, the Citizens’ Climate Lobby hopes to reduce the need for protection against extreme temperatures all-together. This involves tackling climate change at its core by diminishing greenhouse gases.

From a national standpoint, the CCL played a part in creating the Energy Innovation and Carbon Energy Act. Based on their carbon fee and dividend system, the bill imposes a tax on the sale of fossil fuels that is later redistributed over the entire population in the form of monthly income or regular payment. “It essentially puts a price on carbon companies to pay for their emissions,” said Chet Hunt, co-chair of the Knoxville chapters.

The Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act encourages the innovation of clean energy technology and market efficiencies across the country, which will reduce greenhouse gases and pollution to cultivate a healthier and more economically-stable population.

With national support and increasing popularity, Knoxville’s Citizens’ Climate Lobby is pushing even harder for the local government to build climate change projections into its long-term plans. “We are encouraging the city to implement a climate action plan to meet carbon reduction goals. Part of that is putting in measures that protect the low-income community,” Hunt said in an interview.

Programs in partnership with the city exist to provide quick solutions to climate change impacts, but what about the big picture? Putting a band-aid on energy burden and low-income housing may not be enough to protect families from the continual increase of temperatures.

Amending the Tennessee Valley Authority could be a more permanent solution. Established in 1933, the corporation was created to provide navigation, flood control, electricity generation, fertilizer manufacturing, and economic development to the Tennessee Valley. While these initiatives were important 86 years ago, Knoxville now faces entirely different issues.

The TVA mission is becoming obsolete. If updated to align with energy burden and climate change, the corporation could better benefit the city by decreasing vulnerability to extreme temperatures and settling economic unrest for the long-haul.

Climate change and energy burden are hitting Knoxville hard, especially in low-income communities. Their impacts are not being ignored completely, but the local government’s consideration for long-term projections may be lacking. Organizations like ThreeCubed help to pick up the slack, but how long will they be able to tide-over poor families before temperatures and utilities become impossible to tolerate?

Raising awareness for climate change and energy burden could give Knoxvillian’s the power to set the local government’s agenda. Strength comes in numbers, and if the entire population knew of their impacts, the push for long-term solutions would be a successful movement backed by the entire city.